Przewalski’s horses are icons of ancient history and modern conservation efforts. Smithsonian scientists track these animals to understand how they occupy their habitats and to preserve zoo’s historical investment in the restoration of this species.

Height: 1.3-1.5m (4.3 to 5 ft) at the shoulder

Weight: 250-360kg (550 to 800 lbs)

Typically ranging across all of Eurasia, Przewalski’s horses were last observed in the wild in the 1960s before their populations were pushed to extinction from anthropogenic stressors.

Unlike domesticated horses, who have 64 chromosomes, Przewalski’s horses have 66. Despite this difference, the two species are able to successfully interbreed and produce viable offspring.

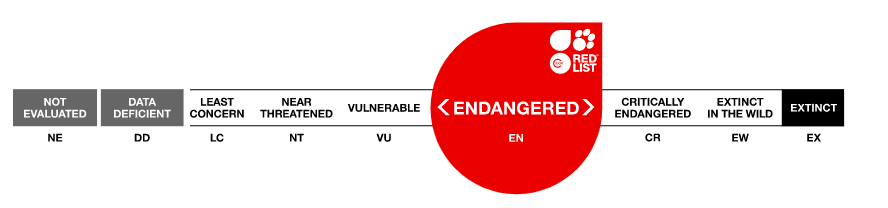

Conservation Status: Endangered

The story of the Przewalski’s horse is a remarkable story of recovery. Last seen in the Gobi Desert during the 1960s, the species was driven to extinction by pressures including competition for resources with livestock, harsh winters, and over hunting. Bred in captivity, the Przewalski’s horse now serves as a symbol for the conservation importance of zoos. During reintroduction efforts to their native ranges, several individuals did not survive the harsh winter, prompting researchers to contact the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) for critical research assistance. To date, Smithsonian researchers have assisted with GPS tracking of reintroduced Przewalski’s horse in the Kalamaili Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China and Hustai Nuruu National Park in Mongolia.

Preliminary tracking results have prompted a variety of questions, including how reintroduced horses utilize different parts of the available landscape, what is the average home range for the species, what environmental factors limit their distribution (e.g., water availability, forage competition from livestock, and predation), and whether or not tracked animals exhibit seasonal shifts in movement behavior. By collaring reintroduced horses, Smithsonian scientists and their collaborators are able to evaluate many of these questions. GPS collaring, however, does have its limitations due to the social structure of this species. Typically, female horses (mares) form harems which are controlled by dominant males (stallions). Groups of stallions (bachelor herds) often exist too, with males fighting for dominance between themselves and with neighboring bachelor herds. GPS collars typically cannot withstand the fights that stallions engage in, often being damaged or worn for very short periods. As a result, most of the data that exists on the movement of Przewalski’s horse is from mares.

Data collected from these collars is providing valuable information about the location of harems, but additional information was needed to understand stallion movements. SCBI is currently conducting non-invasive trials on mounting tail-mounted GPS tracking devices on its captive herd of animals. It is hoped that, if successful, these devices could be mounted on reintroduced animals and provide insight into a entire new window of activit

y about the species.

Along with these technological developments, Smithsonian scientists are tracking 10 horses in Kalamaili National Park and 14 horses in Hustai National Park using GPS collars. Three (3) animals that continue to collect data are show in the animation below.

Director of Science and Conservation

Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI)

Conservation Biologist

Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI), Conservation Ecology Center

Conservation Biologist

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) Conservation Ecology Center

Zhang, Y., Cao, Q. S., Rubenstein, D. I., Zang, S., Songer, M., Leimgruber, P., … Hu, D. (2015). Water use patterns of sympatric Przewalski’s horse and Khulan: Interspecific comparison reveals niche differences. PLoS ONE, 10(7), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132094